“The women . . . put different colored bottles, broken glass and sea-shells all around the grave of Aunt Dicey. In that way they showed their love for her.” William Faulkner, The Day When the Animals Talked

“The women . . . put different colored bottles, broken glass and sea-shells all around the grave of Aunt Dicey. In that way they showed their love for her.” William Faulkner, The Day When the Animals Talked

Even if you don’t call yourself a “collector,” you do inevitably collect things. Often random, everyday things—think of the junk drawer with its assortment of useful items (rubber bands, batteries, children’s safety scissors), broken bits (a headless Lego minifigure, bent pins, a mini-flashlight needing a new battery), and flotsam (mailing address labels received in a charitable solicitation, so many used twist-ties, multiple IKEA furniture wrenches). Sometimes the things you collect have personal significance and family memories associated with them—most of the objects I have from my grandfather are small, handheld things like a tiny red Swiss Army knife, a Mickey Mouse watch with a broken strap, the pocket New Testament that was given to him by a well-wisher before he shipped out to Alaska in World War II, or an unclaimed skeleton key left behind in a coat pocket from his dry cleaning business, and each has specific recollections of time spent with him playing, gardening, visiting him at work, listening to his

received in a charitable solicitation, so many used twist-ties, multiple IKEA furniture wrenches). Sometimes the things you collect have personal significance and family memories associated with them—most of the objects I have from my grandfather are small, handheld things like a tiny red Swiss Army knife, a Mickey Mouse watch with a broken strap, the pocket New Testament that was given to him by a well-wisher before he shipped out to Alaska in World War II, or an unclaimed skeleton key left behind in a coat pocket from his dry cleaning business, and each has specific recollections of time spent with him playing, gardening, visiting him at work, listening to his stories. Sometimes the collections are deliberate and curated—I have multiple sorted jars of beach glass, picked up by me from beaches in North Carolina, Maine and elsewhere but also brought to me by family and friends from Washington, Canada, and New Zealand. Humans cannot go through life without acquiring at least a few of these things, accumulated by chance, time, inheritance, and choice, full of stories but also mysteries, of the presence or absence of a loved one, of the memory of a great day or the broken pieces of a bad one. Why do we hang on to all of these things?

stories. Sometimes the collections are deliberate and curated—I have multiple sorted jars of beach glass, picked up by me from beaches in North Carolina, Maine and elsewhere but also brought to me by family and friends from Washington, Canada, and New Zealand. Humans cannot go through life without acquiring at least a few of these things, accumulated by chance, time, inheritance, and choice, full of stories but also mysteries, of the presence or absence of a loved one, of the memory of a great day or the broken pieces of a bad one. Why do we hang on to all of these things?

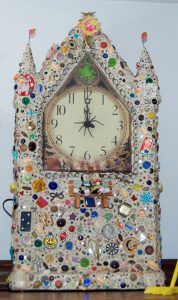

For the makers of folk art “memory jugs,” these small individual objects take on a new and greater significance in reuse, remaking and remembering. A cracked pot, no longer able to function as a container, becomes a surface for invention and art and memorialization with the use of a little cement, glue or plaster, and a great assortment of these little, ordinary, everyday, shiny, broken, dirty, precious things. Common objects appearing embedded in memory jugs include “seashells, glass shards, pebbles, jewelry, mirrors, watches, toys, pipes, hardware, tools, beads, buttons, coins, and scissors.”[1] The pot in the process becomes something else entirely, “colorful and playful, or enigmatic and mysterious.”[2] Very little evidence exists to understand the origins of this practice, whether it comes from the Victorian habit of memorializing the dead through hobby crafts like creating jewelry containing (or substantially crocheted from) the hair of a deceased loved one, of from transplanted West African funerary rituals still performed by African-Americans such as leaving the last objects used by the recently departed on their grave (a teacup, a brush) to prevent their spirits from wandering far from family and memory, or simply from a need to occupy one’s time and hands and using materials readily available.[3] Brooke Davis Anderson, curator of Forget Me Not: The Art & Mystery of Memory Jugs, an exhibition of these unique objects at the Diggs Gallery of Winston-Salem State University in 1996, finds a compelling through-line from Southern ceramic and pottery grave markers (cheaper than stone) and coastal-based societies’ beach detritutus of seashells and colored glass bits to Kongo beliefs in the “watery realm” of the spirit world after death as well as other piecemeal and improvised historic Southern crafts such as scrap fabric quilting and decoupage papier-mâché bottles and bowls.[4] Made mostly in the first half of the 20th century by black and white Southerners alike, memory jugs bring new aesthetic form in their colorful, shiny, knobby, miscellany surfaces to a complex network of relationships within diverse communities as well as a frozen-in-time catalog of the artifacts of a very particular time and place.

and scissors.”[1] The pot in the process becomes something else entirely, “colorful and playful, or enigmatic and mysterious.”[2] Very little evidence exists to understand the origins of this practice, whether it comes from the Victorian habit of memorializing the dead through hobby crafts like creating jewelry containing (or substantially crocheted from) the hair of a deceased loved one, of from transplanted West African funerary rituals still performed by African-Americans such as leaving the last objects used by the recently departed on their grave (a teacup, a brush) to prevent their spirits from wandering far from family and memory, or simply from a need to occupy one’s time and hands and using materials readily available.[3] Brooke Davis Anderson, curator of Forget Me Not: The Art & Mystery of Memory Jugs, an exhibition of these unique objects at the Diggs Gallery of Winston-Salem State University in 1996, finds a compelling through-line from Southern ceramic and pottery grave markers (cheaper than stone) and coastal-based societies’ beach detritutus of seashells and colored glass bits to Kongo beliefs in the “watery realm” of the spirit world after death as well as other piecemeal and improvised historic Southern crafts such as scrap fabric quilting and decoupage papier-mâché bottles and bowls.[4] Made mostly in the first half of the 20th century by black and white Southerners alike, memory jugs bring new aesthetic form in their colorful, shiny, knobby, miscellany surfaces to a complex network of relationships within diverse communities as well as a frozen-in-time catalog of the artifacts of a very particular time and place.

Linda Beatrice Brown, writing in the same exhibition catalog, says of these artworks that their “improvisational use of various seemingly unrelated objects which used again and again in another form, tell and retell the story of lives through the memory jug artists.”[5] This idea can also encompass the practice of creating a museum from a collection, curating an exhibition from a disparate set of objects, and telling their stories to a wider public. Certainly, Forget Me Not provided inspiration for the set of memory jugs that are a part of Jim Massey’s collection in the Small Museum of Folk Art. As Jim himself says, “Art is personal and like collecting anything from marbles to beer cans involves lots of emotions. I come from a long history of collectors. I am sorry that my mother never got to see my folk art collection. She would probably have stopped collecting glass, bottles, antique furniture, plates and platters. . . .” His own practice as a collector is tied up in memories of his relationship with his mother and her varied collections. And the memory jugs are also a product of his personal relationship with the artist, Randy Tysinger, who worked with Jim at Holly Hill Daylily Farm, as well as his activities as a collector, which included acquiring the catalog for the Diggs Gallery exhibition and sharing its contents with Randy. A partnership between collector and artist began, with Jim accumulating small objects and materials from his personal items as well as thrift stores and flea markets and Randy painstakingly piecing together the objects, able to only do a small area at a time until a section of putty would become unworkable. One of the memory jugs (not pictured here) has only shards of glass, pottery and other items found at Holly Hill Farm as the fields were tilled. The largest pot has many of Jim’s own personal items such as a toy car and gun, goofy watch, pen knife, religious artifacts, etc. and took almost one year to piece together and dry. Jim then acquired most of Randy’s pieces, made over the course of only a few years.[6] Randy’s memory jugs are therefore multilayered objects, not just in the physical sense, but in their bringing together of historic folk art practice with folk art collector, museum curation and communication with an individual and inspired talent, and memory-filled and place-specific everyday objects with personal relationships and shared experiences between patron and artist.

[1] Brooke Davis Anderson, Forget Me Not: The Art & Mystery of Memory Jugs, Diggs Gallery at Winston-Salem State University, Winston-Salem (June 1996), p. 7.[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid. pp. 9-13.

[5] ibid. p. 26.

[6] All of the above narrative is courtesy of Maggi Neufer, from an interview with Jim Massey in 2015.